The creative work of Eleanor Suess is hard to categorise as her practice straddles the disciplines of both architecture and art.

Eleanor describes herself as an architect, artist, and educator. As well as working out of her Croydon ASC Art House studio Eleanor is also an associate professor at Kingston School of Art. With qualifications in fine arts and architecture from Australia and the UK, her work occupies a space between art and architecture, often exploring the qualities of her surrounding built environment, from light and shadow to time and space.

I’ve been enjoying following the narrative of her work on Instagram for a while. The cyanotypes (which you’ll recognise from our social media headers) have both a calm and dynamic quality about them, whilst the miniature studio model I find simply mind-boggling. I caught up with Eleanor to discuss her work in more detail and to hear whether lockdown has influenced her practice.

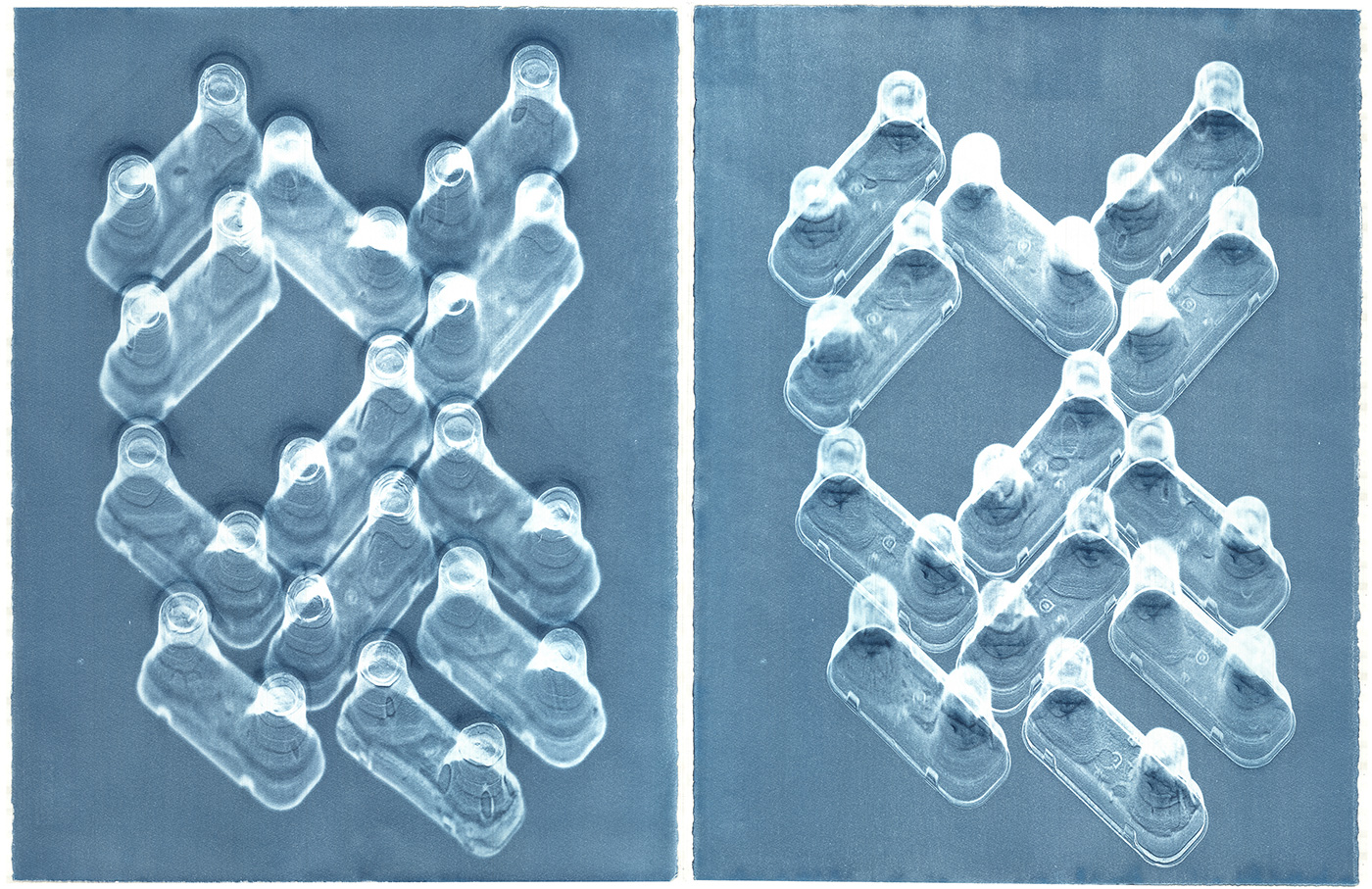

Avocado Packaging Cyanotype 4 and 5 Diptych

Croydonist: First of all, are you a Croydon native or convert?

Eleanor: I am a Croydon convert, but of all of the places in the UK, Croydon is where I call home. Outside of the UK, Perth, Western Australia is “home” for me. We moved there from Leeds when I was nine, and so it’s where I grew up. I think the quality of light in Perth is something that has deeply influenced me and may be why all of my work uses light in some fundamental way.

Croydonist: Do you see yourself firstly as an artist or an architect and how does one inform the other for you?

Eleanor: Neither discipline is primary for me, and it is that in-betweenness, and disciplinary fluidity, which is critical to how I work and what I make. In my practice I combine techniques from both architecture and art, to develop methodologies which are “transdisciplinary”– in this I use Zachary Stein’s definition, which emphasises the equal relationship of both disciplines. The performative nature of both disciplinary practices produces hybrid processes of making, which may in part be recognisable to each discipline, while remaining slightly “other”.

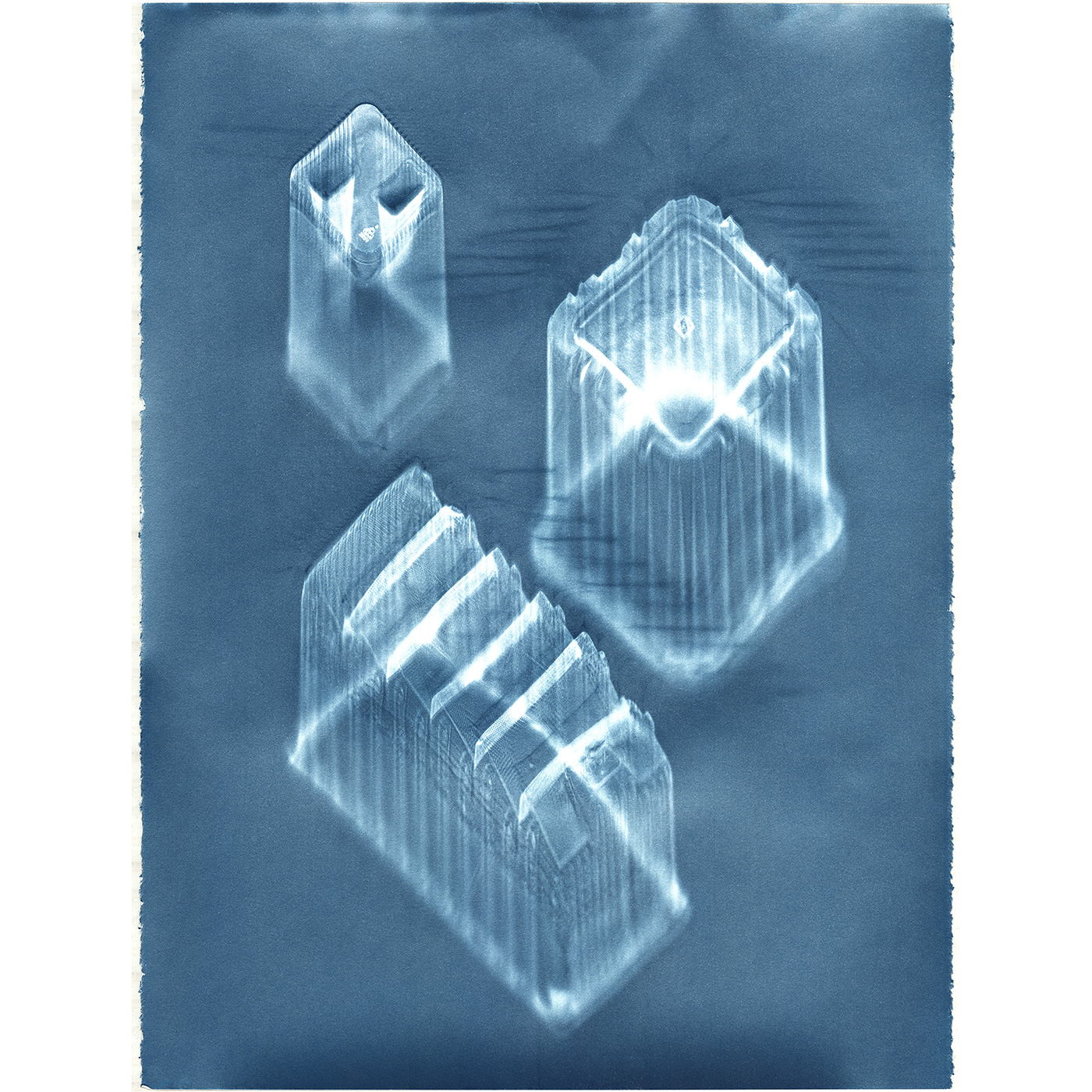

Plastic Packaging 1 cyanotype

Croydonist: How did you get to where you are today?

Eleanor: I’ve had a rather complex journey, through different countries and different disciplines. My first degree is in fine arts, which I studied in an architecture school, taking some of the architecture classes. This enabled me to gain my undergraduate architectural qualification after another 18 months of study. I then came to the UK for my mid-training practice experience, or “year out”, and wound up staying. After finishing my architectural qualifications here, and working as an architect in various practices, I began teaching. Throughout my architectural studies, processes of making that I had started as a fine art student continued, in various forms. As an academic researcher I have been able to develop my practice, and to produce academic papers which help to contextualise the work I make in the studio. Through a practice-based PhD at Central St Martins (which I am in the final stages of completing) I have been able to expand my practice, and to more fully understand its relationship with its “parent” disciplines.

Croydonist: As an educator, does teaching influence how you work as an artist?

Eleanor: Teaching is a big influence on my work, and my work has a similar impact upon my teaching – this is the ideal relationship between the academy, and the external, professional practise of its teachers. My work with architectural models has been strongly influenced by the significant use of models in the architecture courses at Kingston School of Art. Being surrounded by these models, and helping students to develop their projects through such artefacts, has clarified my understanding of the relationships of architect and viewer respectively to physical models and their photographs. It is this that led me to develop methods for filming models. I integrate this, and my cyanotype work into my teaching, through several postgraduate architecture and landscape modules.

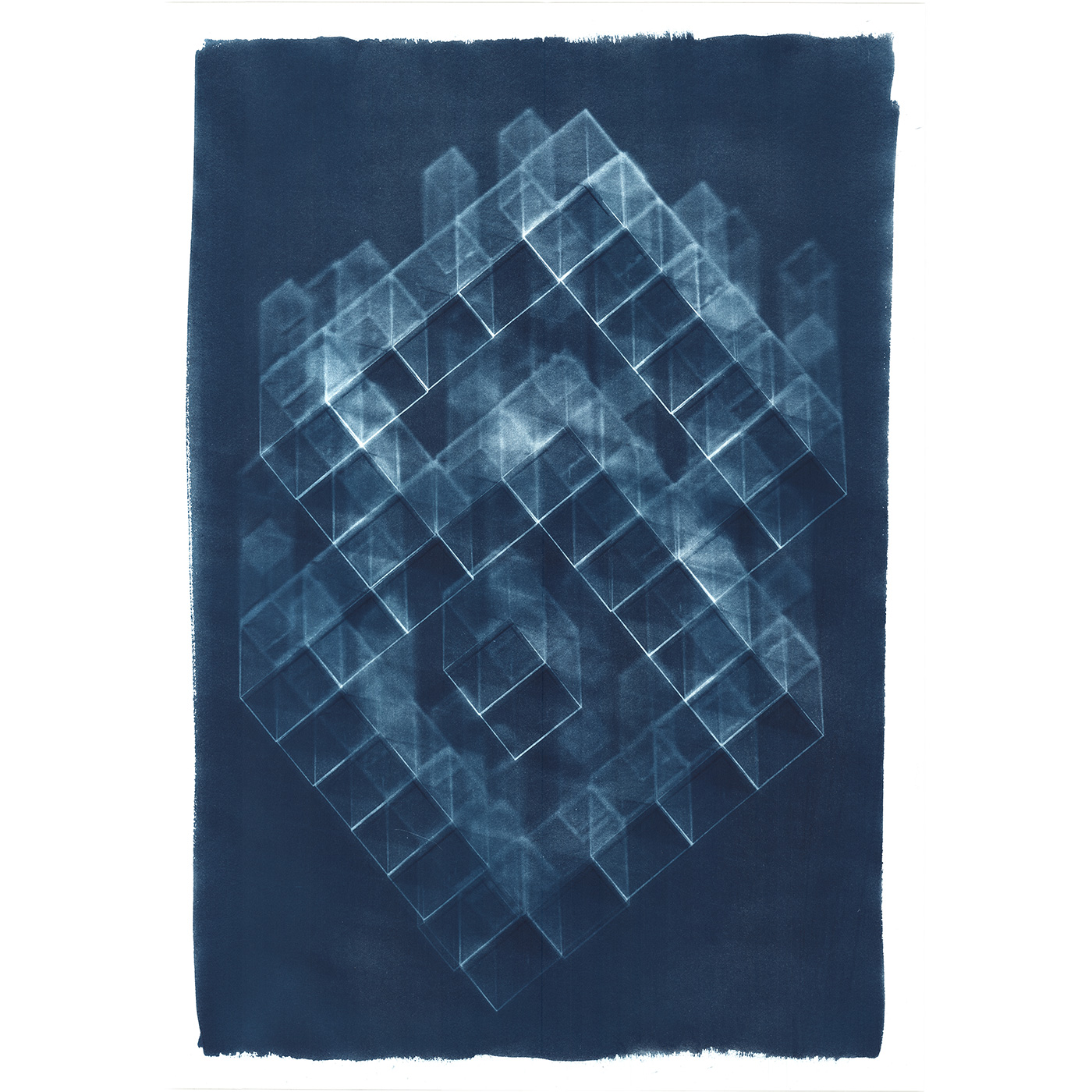

Axonometric Portrait 8 Cyanotype

Croydonist: As your work is often site-responsive, how does your studio in Croydon specifically inform your current work?

Eleanor: The site responsive aspect of my practice is one of the architectural elements of my process – good architecture starts with site, and an understanding of place through forms of documentation and research. When I first saw my studio when the Art House complex was taking residents, I knew that it would provide a wealth of material for my work, as well as being filled with the sunshine I need for my cyanotypes and model filming. The view of the factory wall occupying the adjacent site became the most immediate element to respond to – I started filming it the day I moved in and have produced several pieces about the changing character of this brick wall. This work ranges from a moving image installation for the inaugural studio exhibition, “40º Celsius”, though to edited artists’ films.

In fact, I would say that all of my work is responsive to found conditions or objects. Even the work with cyanotypes (that I will discuss a little more later) always starts with something found.

Croydonist: How has the lockdown affected your work?

Eleanor: Fortunately, the company that runs the studios has been able to keep them open and they have implemented rigorous processes to limit any opportunity for contagion. As I work in my studio alone and can drive from door to door in five minutes, I am able to use the studio for aspects of my work that I cannot undertake from home. Before visiting the studio for the first time in the lockdown I did what I know from being an architect – I undertook a risk assessment to be sure that I would not be contributing to the spread of the virus. I feel very fortunate to have this extra room that I can occupy, now that our worlds are so very small.

Studio F23 actual room

Croydonist: I am fascinated by the development of your replica model studio I’m following on Instagram – what’s the story behind it?

Eleanor: This project was initially conceived more than a year ago, and since then I have made two similar site-specific models within the rooms that they replicate. One was in a studio at my old art/architecture school in Perth, when I was there for a Christmas visit, and the other was at a group exhibition at the Phoenix gallery, Brighton. The risk of being prohibited from using my Croydon studio in the Covid-19 crisis provided the project a sense of urgency, and then conducting it in the lockdown gave the act of undertaking this solitary work to make a replica of my physical workspace another layer of significance. My world has shrunk to my home and the studio, and all of my professional and personal interactions (beyond my partner) are via mediated technology, bringing us virtually into each other’s homes. In this context I have built a physical “virtual” version of one of my two “real” worlds, understanding more and celebrating the material nature of this precious space.

Studio F23 model

These model reconstruction projects are fundamentally about the nature of architectural representation, and the perceptual construction of “space” in viewing model photographs and films, and the viewer’s potential physical relationship with a scaled version of the room in which they bodily inhabit. The current project to make a 1:15 scale paper and card model of my Croydon studio takes this further, through the construction of a model of the model (so at 1:225 of the real room), and then a model of that model of the model of the room. The final version is at a scale of 1:3375 (1:15 to the power of three) and is only several millimetres on each side – it is nothing more than a small piece of grey-board. But the views of the model inside the model lends an extra layer of ambiguity, of uncanny “doubling” to the imagery which I feel is part of all model imagery (it is read simultaneously as real space, but also understood to be a model). This work is also about the performative nature of making the model, of being inside the 1:1 “real” room which is being replicated at a smaller size – this is why I film myself making the model, so that this process can become part of the final artwork. All three of these projects also use a view of the “real” world beyond the models’ windows – despite the scale difference, the juxtaposition of model and real space is not jarring but does lend the imagery an additional layer of uncanniness.

Croydonist: Do you have a favourite artwork to date?

Eleanor: I’m currently really enjoying working on the studio model project – I feel it has so much potential, and I have lots of ideas of what to do next with it. I am seeing the model as a new site in itself and considering how to make work within this space. My work is so much about process that I tend to really like the in-progress work. Once it is finished, and I have moved on to the next project I feel less connected to it. I have some of my favourite cyanotypes hanging in my studio, which I rotate as I make new work. This allows me to continue to reflect upon them, and it often sparks new ideas.

That said, I am very pleased with a film I made in 2017 – “Carriage” – edited from footage taken out of a train window at night. It keeps on receiving screenings at film festivals (or did before these things all stopped!), and in writing about it for my thesis has allowed an extra layer of reflection and understanding but at a necessary critical distance. Sometimes I feel that I only fully understand what I was doing with a project much later. I still have some favourites from points in the last 28 years of my practice – I recently digitised a VHS video that I made while in art school in 1993 (and hadn’t seen for at least 20 years!), and as well as a strong sense of nostalgia I found the work to still be very relevant to my current practice.

Croydonist: I love the dynamism of your cyanotype blueprints. What’s the process to create them?

Eleanor: Cyanotype is a form of very early photography, invented by Sir John Frederick William Herschel in 1842. The “Prussian blue” colour of the prints is a result of the chemical processes at work in this technique. In early photography this colour was thought to be too strong for landscape photography, and so at the time the cyanotype process was mostly used for reprographic copying purposes. This led to the term “blueprints” for architectural and engineering drawings. The cyanotype process is now predominantly used for alternative photography and art practice.

I have been using the cyanotype process for several years, and have made work which ranges from full-sized “photogram” prints of found objects and architectural space. In the summer of 2018, I was artist in residence at the Croydon Arts Store Research Space and made a series of very large fabric cyanotype prints of the shadows cast by the Whitgift Centre’s glass roof structure. I am particularly interested in the relationship of the blueprint to architectural representation, and through my work have demonstrated that the shadows of objects cast by the parallel rays of the sun produce a particular type of architectural projective drawing, called the “axonometric”. I have been using this understanding in my studio to make photogram prints from acrylic hollow cubes and solid blocks, constructing assembled architectural “models” whose shadows, reflections and refractions are captured and frozen by the UV sensitive cyanotype coated paper. I have also been making cyanotype photogram prints of single use plastic packaging, treating these found objects as architectural forms.

Croydonist: Classic interview question – if you had to invite a famous artist, a famous architect and a famous educator to a drinks party, who would they be, and what would you all drink?

Eleanor: Actually, I don’t think I can select individuals – in my work, especially in my experience as an architect, but also fundamentally as a teacher, collaboration is vital. While my own art/architecture practice is largely solitary, I don’t subscribe to the hero individual creator model. One of the things I love most about teaching is working with my colleagues – both staff and students, to collectively produce knowledge. I have had so many experiences where in working with others we are so much more than the sum of our parts.

But we would drink margaritas, or maybe martinis, or a good Islay single malt…..

Whitgift Cyanotype

Croydonist: What’s next for you this year?

Eleanor: For the foreseeable future plans will have to be necessarily modest, and the work achievable from home or my studio. However, a more ambitious project that I was intending to start properly planning and seeking funding for later this year, is to extend the work that I did in the Whitgift Centre. When I conceived it the Westfields proposal was still going ahead, and the original building was to be demolished. I wanted to produce a larger and expanded series of cyanotype shadow portraits of the space, which could act as a permanent memory of the place, a trace of its ghost perhaps, after it was demolished. I hope that at some point I will be able to realise this project.

Thank you to Eleanor for chatting to the Croydonist. Find out more about her work on her website, and follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

All imagery courtesy of Eleanor Suess. Header image, crop of Factory Wall still.

Posted by Julia

No Comments