Concrete. To some, it’s synonymous with Croydon. Our reputation for concrete car parks, concrete high-rises and concrete flyovers precedes us.

Many of our most striking buildings in the town centre are inspired by brutalist architecture. I say ‘inspired’ as some are actually too decorative to be truly defined as brutalist (think of No. 1 Croydon’s mosaic tiles…)

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the term, brutalism is an architectural style which spanned the decades between the 1930s and the 1970s. The name originates from the French for ‘raw’, as the architect Le Corbusier described his chosen building material as raw concrete (béton brut). Brutalist architecture is seen as functional, thus the structure of the building is exposed, rather than hidden with pretty facades.

This month RISE Gallery presents ‘A Journey through Brutalism’, an exhibition which plays homage to brutalist architecture, particularly the buildings in our borough.

A few days ago I was lucky enough to be shown round the show by curator Nicola Charles.

Before you even enter the gallery, through the window you’ll see Charlie Lang’s two concrete sculptures which loom over the exhibition space, much like a brutalist building stands over urban Croydon. You can walk beneath one, as the slabs twist and turn from floor to ceiling. (Don’t worry the slabs above your head are actually made from polystyrene). The other smaller structure towers up like some concrete game of Jenga balanced precariously on wheels. They both feeling to me like brutalism might be in flux – a style that can turn in or out of fashion – loved or hated by the people.

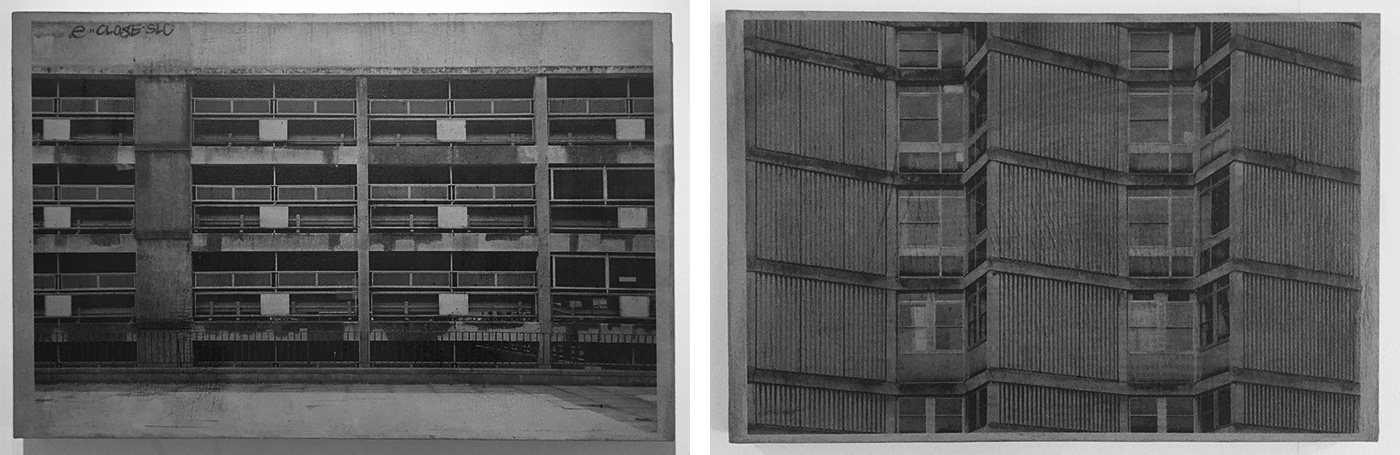

Looking to the wall on the left you have a grid of nine black and white prints by Glen Foster. The photos shimmer as if the buildings are glinting in the sun, thanks to the crystal archive pearl paper on which they are printed. And yes you can play ‘name the Croydon landmark’.

On the back wall sits Adam Halliday’s trippy depiction of No. 1 Croydon – this is meticulously painted onto wood. Halliday has created various different coloured versions of No. 1 Croydon, but this black and white one feels at home in this largely monochrome exhibition.

On the right-hand wall are prints of College Road car park and the Former College of Art by Charlie Henson (shown above). On closer inspection you realise the photos are actually printed on concrete – no mean feat I’m told. Both pieces force you to examine the repetitive nature of the buildings – ironically becoming stark decoration on the slabs.

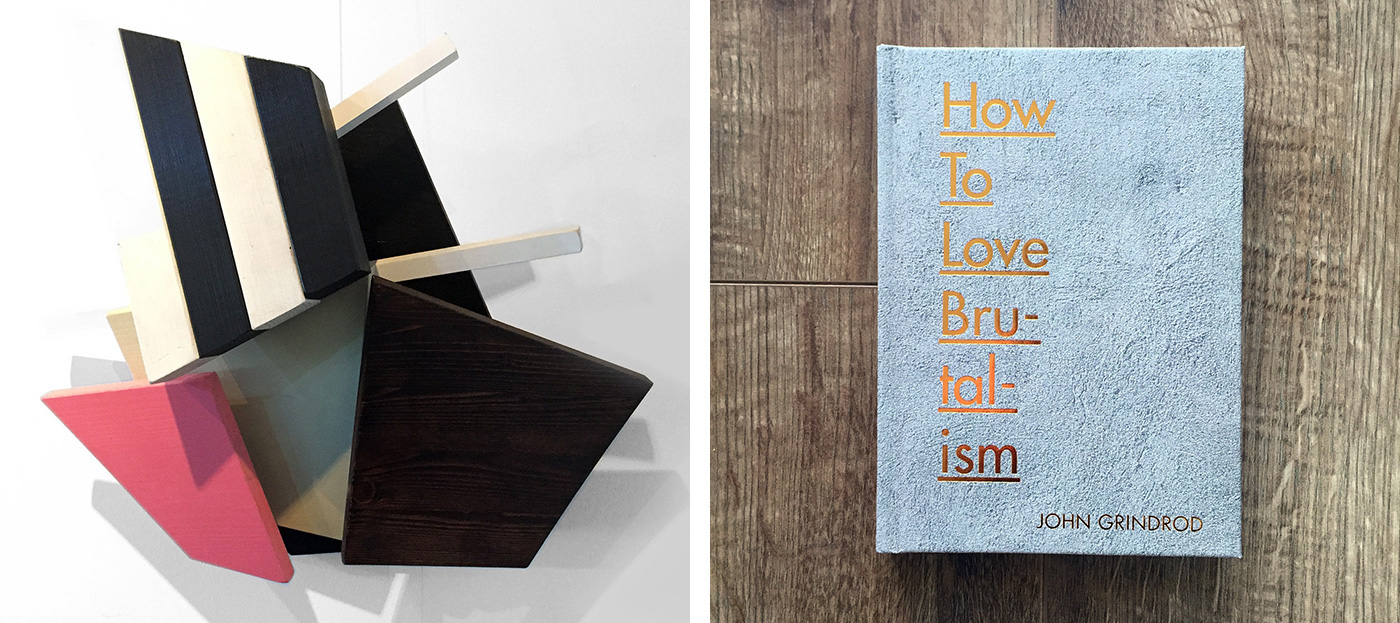

Opposite Henson’s work, two geometric wall sculptures pop out at you. These painted wood artworks by Mark Mcclure are the only zing of colour in the space – like allsorts amongst a bag of licorice.

Before you leave the space take a moment to watch Laurent Bompard’s quite mesmerising isometric animation – reminding me of how the past depicted the future, rather like some of Croydon’s 60’s space-age architecture.

I found the show a charming and playful take on brutalism, carefully put together by people who evidently love the style, like I do.

An added bonus to the show is that you can also pick up an advance copy of Croydon author John Grindrod’s new book ‘How to Love Brutalism’ published by Batsford. A book that is both a cracking read so far, and a visual feast – complete with concrete texture cover designed by Ana Teodoro and aptly illustrated by The Brutal Artist.

‘A Journey through Brutalism’ is accompanied by a series of brutalist walking tours supported by the National Trust. We are booked on one this weekend so if you love Croydon’s concrete architecture check out our Instagram for pictures.

The exhibition continues at RISE Gallery until 31 March.

Posted by Julia

This reminds me of the publication we produced for the National Theatre, Concrete Reality, Denys Lasdun and the National Theatre. The same architect also had is hand in the Royal College of Physicians building.